Cappadocia (pronounced Kapadokya) has long been on our bucket list. A land of fairy chimneys, rock monasteries, and underground cities, it captured my interest and imagination the first time I saw pictures of it. It is located in Central Anatolia in Turkey, and it was our next stop after Istanbul. We steeled our nerves and caught our second European night bus for 60 Turkish lira per person (including a shuttle from our hostel to the Istanbul bus station) to the backpacker-friendly town of Göreme, our stunning home base for exploring the Cappadocia area.

Our gorgeous cave room in Göreme

While our plan was to explore the region on our own, we decided to take the ever-popular “green tour” to see some of the more remote attractions in southern Cappadocia. Typically, we try to avoid guided tours like the plague since they so often mean high price tags, large groups, being rushed through activities, and too little time. However, we reasoned that this tour would be the easiest way to see some of the harder-to-get-to attractions in the area. You can book this tour through your hostel (which is what we did) or through any of the countless tourist agencies littering the streets. We paid 80 lira per person.

So… what did this get us?

History

The rocks of Cappadocia have felt the feet of many cultures… the Phrygians, Assyrians, Hittites, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Seljuks, and Turks to name a few.

But that’s not what makes them one of Turkey’s largest tourist attractions. The strange and enchanting landscape created through volcanic activity and natural erosion – combined with the monasteries, churches, and dwellings carved into the towering rocks – is what brings over two million visitors to the area every year.

The valleys of Cappadocia, which means “land of the beautiful horses,” were a refuge for early Christians fleeing from oppression and death by Roman soldiers. When Emperor Constantine “Christianized” Rome and granted religious freedom to Christians, the secluded region became the perfect place for Christians to remove themselves from society and devote themselves to worship.

The rock churches began as dwellings for Christian hermits, and later became larger monasteries after St. Basil (who has born in the region) convinced them that they would better serve the will of God by focusing on a communal life of prayer.

The earliest frescoes in the churches were painted with red dyes directly on the rock. Later frescoes were painted on a layer of plaster with various coloured dyes, then glazed with the whites of pigeon eggs. The vast majority of the frescoes now have images with destroyed faces and/or eyes. Our guide told us that there are several theories about this. One is that the Greeks that left the area in the population exchange of the 1920’s carefully scratched out the eyes and took them as souvenirs. This seems unlikely. The more popular opinion is that the Qur’an prohibits images of humans in temples, so when the churches were later converted into Muslim mosques, the images were purposely destroyed.

Religious frescoes with eyes scratched out

A View of Pigeon Valley & Uchisar Castle

We were promised a stop at the Uchisar Castle and that’s precisely what we got… a stop. Our van pulled over at a panoramic viewpoint and let us out just long enough to hear some of the above history and snap a few photos of Uchisar Castle and the surrounding Pigeon valley (so named because pigeons were so important in the area – they were used to send messages, their egg shells were used in the making of plaster, and the egg whites were used as a protective glaze for the painted frescoes).

One of the volcanoes that worked to create the surreal landscapes of Cappadocia

Uchisar Castle

Pigeon Valley

Dwellings and churches carved into the rocks

Derinkuyu Underground City

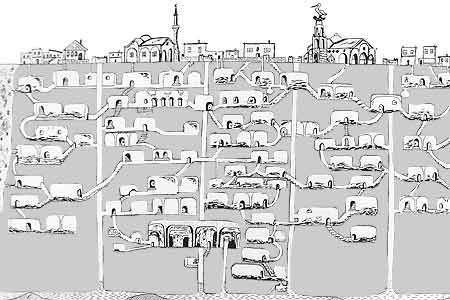

This is where the tour got good. Derinkuyu is the largest of about 40 underground cities in Cappadocia. It was first built by the Phrygians between the 8th and 7th century BC, then enlarged by the Byzantines between the 5th and 10th century AD.

It extends 8 levels (or 85 m) under the earth (apparently there are possibly 3 more levels yet to be excavated). There are something like 600 outside doors that lead to the city from surface dwellings. It was never a permanent dwelling, but was used as a hide-out for local populations when invading armies arrived. Between 20,000 – 50,000 people and their domestic animals could live in the city, and it was connected by tunnel to another underground city 10 km away.

The rooms consisted of churches, stables, kitchens, storage rooms, wineries, cellars, refectories, and living spaces. On the second floor there is a large room with a barrel vaulted ceiling that is unique to the underground cities in the area. It was used as a missionary school. On the bottom floor, there is a crucifix-shaped church. There are chimneys, ventilation holes, and niches in the walls for oil lamps. Only about 20% of the city is open to the public, but trust me… it’s enough to get a feel for how huge of a structure it actually is.

In the event of an attack on the city itself, doors could quickly be sealed with large round stones. Traps were built into the design, including covered holes in the floor and holes in the ceiling that spears could be thrown through. The city had numerous wells, many of which did not have surface access to prevent poisoning from above.

Well with surface access. Used as a concealed ventilation shaft.

I expected it to be musty and hard to breathe so far underground, but the city’s 15,000 ventilation ducts do a good job of keeping the air fresh.

Underground rooms

If you want to go on your own: Derinkuyu Underground City is located in the town of the same name, Derinkuyu. It is about 40 km from Göreme. Admission is 15 lira/person. Bring a jacket – it’s can be quite chilly underground, even on a hot summer day. Not recommended for people with asthma, heart conditions, or claustrophobia.

Lunch & Hiking in the Ihlara Valley

Ihlara Valley is the longest and deepest gorge (1oo m) in Cappadocia and home to some of the oldest rock-cut churches in the area.

Ihlara Valley

We stopped in a village in the valley for lunch. Lunch was large, but forgettable… it included bread with honey and tomato tapenade, lentil soup, a main dish, rice, salad, and an orange.

After the meal, we drove to the second of four entrances of the 14 km long valley. We descended over 300 steps to the valley floor and hiked about 4 km along the river. Here we saw more churches and dwellings, but mostly took in the magical lighting and vibrant autumn colours around us.

Frescoes in church

Break time!

Duck stretching its wings in the river

Hiking along the valley floor

If you want to go on your own: Hiking the valley is easy, but getting there is hard. From the best of my research, it seems you can get to the valley from Göreme (120 km) via public transportation, but it will take you 2-3 bus transfers and the better part of a day. There is an entrance gate to get into the valley (at least the portion we hiked). Admission: 8 lira/person.

Selime Monastery

At the end of the Ihlara Valley towers the Selime Monastery in Selime village. The Selime Monastery was carved by monks in the 13th century and is the largest in the Cappadocia region.

Selime Monastery

Fresco

View from monastery

Detail of building, including pigeon holes

Interior of church

Impressive interior design

For all you Star Wars fans out there, the surrounding area was used for some of the Sand People scenes in the original movie (only the scenery was filmed, the actual action was shot in Tunisia).

Sand People scenery

If you want to go on your own: Selime Monastery is located in Selime village. The only way to explore the monastery is through a fairly steep climb up the rocks. Bring good shoes and consider avoiding it in rainy weather when the rocks can be slick (if it’s raining when you go on the tour, they don’t allow you to climb the rocks). Entrance: 8 lira/person.

So Was the Tour Worth It?

As with all tours, we felt rushed… we had almost enough time at Derinkuyu, but were definitely rushed through Selime monastery. It would have been nice to see more of Ihlara valley, though we wouldn’t have had enough daylight hours to really make that happen anyways. If the tour had left a little earlier (we were picked up at 9:30 am), we could have had more daylight hours for hiking. As it was, we were back at our hostel by 5:30 pm. Note: Due to daylight savings time, the sun rises at about 6:00 am and sets at about 4:30 pm in early November.

Though we were rushed, we got lots of good information from our guide.

9D Cinema?!?!?! This is something we would have investigated had we had the time

There is really no information at any of the sites, so we learned a lot more from our guide than we would have got exploring on our own. As I mentioned, the tour cost 80 lira/person. We would have spent 31 lira/person on entrance fees alone. Factoring in lunch and transportation, we probably couldn’t have done it much cheaper ourselves. And, it certainly made it easy to see the more distant Cappadocia highlights. The group size was reasonable (about 10 people). We were happy with our experience and would recommend the tour to others.

View from our rest stop on the way home.